In this week’s newsletter, we bemoaned the fact that life expectancy rises are grinding to a halt in England. The story broke a few weeks back and quickly disappeared from view, barely remaining in the news long enough to kickstart a conversation.

But the question of why, after a century of continuous progress, the upward trend of rising life expectancy is now stagnating must be addressed. While University College London expert Sir Michael Marmot suggested that government budget cuts might be to blame, clearly there are many factors influencing the matter.

What the Figures Tell Us

In the last 100 years, life expectancy across the United Kingdom increased from 46 to 81 years. However, since 2010 the rate of increase has almost halved. Perhaps more troubling is the fact that British women now have the second-lowest life expectancy in western Europe.

The “levelling-off” of historically ascendant life expectancy rates is to be expected eventually, of course: it’s difficult to envisage a discovery which will lead to humans living for 150 or 200 years, so there is a natural endpoint to the trajectory. But few anticipated this stall occurring quite so soon. After all, less than a year ago human lifespans were said to max out at around 115 years. We are some way off hitting the ceiling.

Social determinants are undoubtedly a factor in influencing lifespan statistics. On average, men living in areas of higher deprivation in England can expect to live nine years less than their counterparts in the least deprived areas; for women, the gap is seven years. But is it the whole story? With smoking rates at an all-time low, and cancer survival rates at an all-time high, some people are understandably at a loss to explain the statistical sloping off.

How Can We Increase Life Expectancy?

However, when you consider factors such as poor diet and increasing cases of obesity, high levels of stress, environmental contamination and the overuse of prescribed medications, the plateau in life expectancy is really not so surprising.

In recent decades, our environment and food supply has undergone tremendous change, with consequent impacts on longevity and quality of life. The ingredients for a healthy life are no great secret: nutritious food, clean water and exercise are the cornerstones. Not smoking is hugely important, as is limiting your intake of alcohol and toxins.

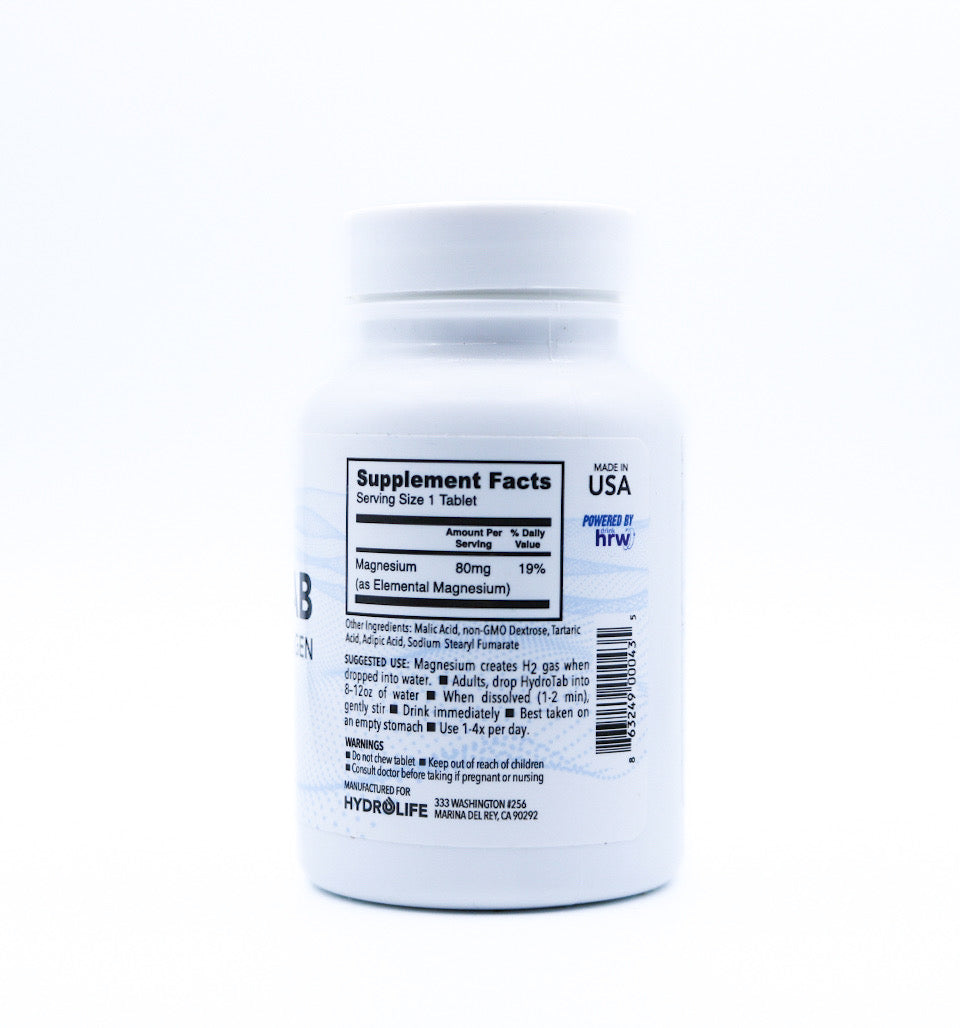

Educating oneself as to the dangers associated with over-medication, and the benefits of sensible natural supplementation, is in our view highly important. To be clear, it is not accurate to say that all prescribed drugs are dangerous or detrimental and all non-medical therapies are unfailingly helpful. Rather, we should be mindful that many western medicines are created in laboratories using chemicals which are foreign to the human body; what’s more, there is a mountain of evidence showing that certain drugs negatively affect the performance of our immune systems in fighting pathogens and viruses.

Non-pharmacologic health interventions are, on the whole, preferable to treating symptoms of illness with drugs pushed by profit-minded pharmaceutical companies. Thankfully this is something which is gradually becoming more accepted.

At this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, Psychiatry Professor Dr. Lon Schneider admitted that reducing dementia risk factors would have a far greater effect than “current, experimental medications.”

Dr. Schneider also noted that antipsychotic drugs generally prescribed for cognitive conditions heighten one’s risk of cardiovascular problems and even death.

Official figures show that food supplements and herbal remedies are, by some margin, the safest substances consumed by UK citizens; in fact, adverse reactions to pharmaceutical drugs are 62,000 times more likely to kill than food supplements, and 7,750 times more likely than herbal therapies.

Few could deny that a more natural approach to health is finding its way into the mainstream. The BBC programme Doctor in the House is just one example of this attitudinal shift. As Dr. Rangan Chatterjee says, “Most of my patients don’t need a pill, they need a lifestyle change.”

Even the British Medical Journal has rallied against conventional healthcare; their Too Much Medicine initiative intends to highlight the threat to human health posed by over-diagnosis and the “waste of resources on unnecessary care”. This approach has many different names: integrative medicine, functional medicine, progressive medicine.

It is built around proper dietary advice (centred on whole, unprocessed foods, proteins and healthy fats), a suitable exercise programme, stress reduction, sleep and sun exposure. Lifestyle interventions are the pathway to improved health and wellbeing, not unnecessary prescriptions. Obesity, type 2 diabetes and inflammation can be significantly improved and even reversed by following this synergistic, whole-body approach.

What the life expectancy figures show, however, is that there’s a long way to go. In the years ahead, we would all do well to take personal responsibility for our wellbeing. By creating the right conditions for our health to prosper, we will surely surmount the lifespan plateau and, like the population of South Korea, continue towards an average life expectancy of 90 within the coming decades.

Leave a comment